An interview with Hirohiko Araki detailing his visit to the Louvre included in the Japanese hardcover edition of Rohan au Louvre, titled HIROHIKO ARAKI Meets MUSÉE DU LOUVRE, published on May 31, 2011.

Hirohiko Araki Meets Musée du Louvre

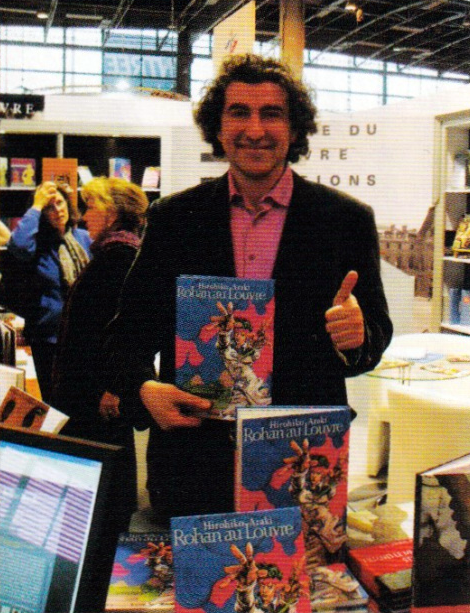

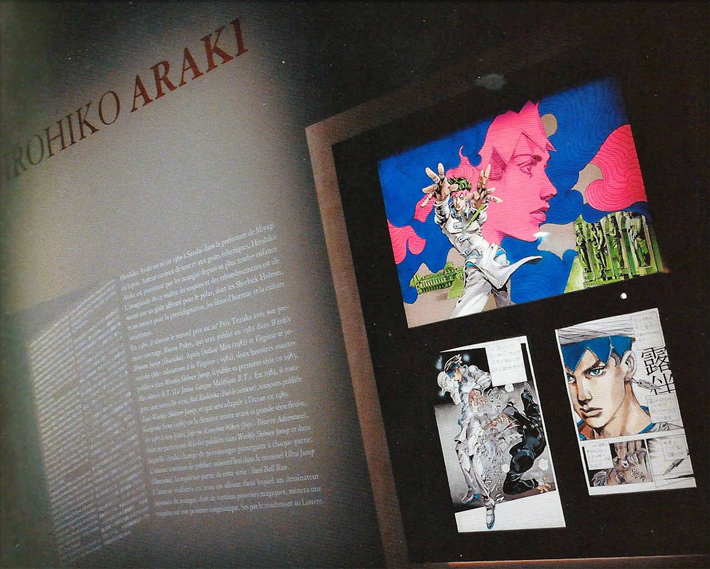

In January 22, 2009, we saw the unexpected collaboration between the world-renowned French museum, the Musée du Louvre, and the Japanese manga artist Hirohiko Araki. It also marked the first time in history that the Louvre—host to many famous works of art, including the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo—has exhibited works from a Japanese manga artist. During the exhibition, Araki announced that he would draw a full-color manga as part of the fifth book in the Le Louvre invite la bande dessinée project.

Bandes dessinées, abbreviated to BDs, is a term used to describe comic books published in French, often illustrated by French artists. In France BDs are widely considered an art genre, separate from American comics and Japanese manga. Le Louvre invite la bande dessinée (translated into English as “The Louvre Invites The Comics“) was a project that sought to introduce the fantastic world of comics to a larger audience by collaborating with various French and foreign authors. The authors would then have their original works published and exhibited at the Louvre.

About a year before the exhibit started, Araki received an invitation from Fabrice Douar, deputy editorial manager of the Louvre’s publishing department, who was looking for a Japanese manga artist to fill the role of the project. The only conditions for the project were that the work had to center around the Louvre and that it had to be entirely original (e.g. not using pre-existing characters).

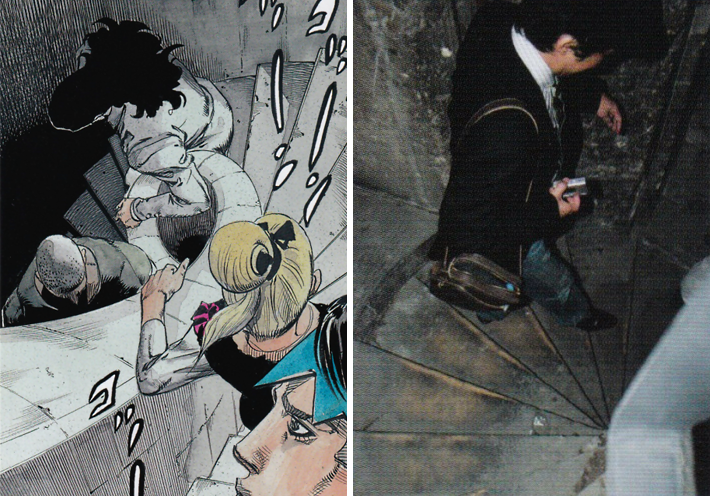

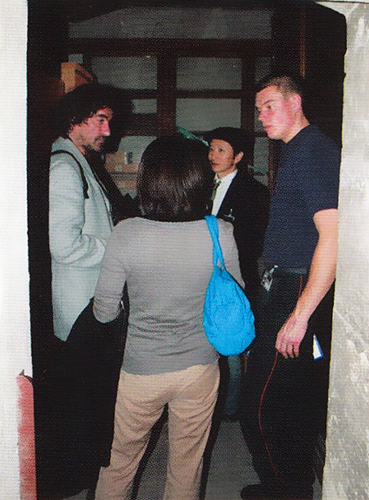

In Fall 2008, Araki was taken on a private tour of the Louvre while it was closed. Araki had visited the Louvre countless times (he even held his own solo exhibition in Paris four years prior). However, this was the first time he was allowed to enter the museum’s lower levels, including the basement, which is inaccessible to the public. During the tour, Araki came up with the idea of featuring a manga artist, similar to Rohan Kishibe, pursuing a bizarre painting kept in the Louvre’s vast collection of artworks. Inspired by this idea, Araki finished a draft for the story and completed the first four manuscripts ahead of time, which were featured at the exhibit.

The Louvre originally asked Araki to join the project because they wanted him to draw a black-and-white manga to show the differences between the French and Japanese styles of making comics. However, Araki decided to make it full color, something he had never done before. In 2009, the 123-page work titled Rohan au Louvre (translated to English as “Rohan at the Louvre“) was completed in full color, featuring a story that bridges the gap between Japan and Paris through the Louvre. It was planned to be 60 pages long but doubled once Araki decided to include the first part of the story set in Japan.

Under the Louvre

According to Araki, the key process to creating his stories is visiting the places he wants to feature. He says, “Being able to go to a place and get a feel for the setting myself, being able to see and touch it, I think this is what makes my drawings more convincing. I’ve been to the Louvre many times, but going there to see the art and going there for a private tour are completely different things. It also changes my perspective on the whole place.”

Upon entering the Louvre’s offices, Araki was greeted by the aforementioned Fabrice Douar and Masami Sakai, who acted as his interpreter during the tour. It’s a little-known fact that the Louvre employs trained firefighters, which are on duty at all times of the day. This is to ensure the safety of all persons and property within the building. As Araki entered the off-limits parts of the museum, two of these firemen were required to escort him. In the story, Rohan is also accompanied by two members of staff and two firemen as he goes down into the Louvre’s basement.

Since the Louvre was too large to cover and contained countless artworks, Araki chose to limit himself to one part of the building. For his story, he decided to focus on the basement of the Louvre, an inaccessible part of the museum where one might expect to uncover something disturbing. While discussing the basement, Araki said, “What intrigued me the most was how you would get into the basement. Do you take the stairs? An elevator? How long of a stretch would you have to walk? I wanted to know where the light switches were, how dusty the place was, and what material the walls were. Those are kinds of things I thought about.”

Due to the building’s age, the only way to get down to the basement was through a dimly lit set of narrow stairs. It was vast and expanded out into a complex labyrinth of hallways. Overall, the basement had been well-maintained over the years. However, there were a few areas left tattered and untouched. Even the staff didn’t know the full extent of the underground, and there were many places that neither Mr. Douar nor Ms. Sakai had ever set foot in.

Continuing through the basement, they found an old abandoned storage room. Because the Seine River—which runs near the Louvre—flooded due to global warming, all the artworks stored in that room had to be moved to another facility. The only thing that remains is an empty stone room with bare wooden shelves, which would be the basis for the “Storage Z-13” room as seen in the story, although no such room with that name exists. The room was full of mystery as if some mysterious painting or mythic artwork were hiding there, waiting to be discovered.

While Araki discussed the idea of an “evil painting” during his tour of the deserted museum, he saw all sorts of strange paintings with disturbing or intriguing origins. Unsurprisingly, there was no such thing as a cursed painting, to which Douar mischievously responded, “The Louvre has the largest collection of artworks in the world. With such a large collection, something like that is sure to exist.”

Full Interview

Firstly, please tell us how you came about getting involved in this project.

Araki: It all started because of a conversation I had with Akiya Takahashi (the founding director of the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum) while I was helping him with his “Musée d’Orsay” exhibition (“Musée d’Orsay: A 19th Century Artists’ Paradise” held in 2007). He told me that he had heard about the offer through a newspaper company, which is how I got involved.

What were your thoughts when you first heard about the offer from the Louvre?

Araki: I felt honored, but at the same time, I felt like it was too good to be true. (laughs) I was like, “Really, the Louvre?” (laughs) When you think about the Louvre, Japanese manga isn’t something that comes to mind. But when I found out the offer was true I felt honored. I’m also grateful to all the people at the newspaper company who acted as my intermediary, even though they really had no incentive to.

This was your first work in full color. Was that something you planned from the beginning?

Araki: I heard that the other authors involved in the project were doing full-color, so I figured I might as well do it too.

When Fabrice, the project curator, visited Japan to see your black-and-white manuscripts for Steel ball Run, he said: “[manga] has a certain appeal that’s impossible to ignore. If you want to push the Japanese style of making comics, I think it would be great if you drew it in black-and-white.”

Araki: Thank you. That was definitely an option, but since opportunities like this don’t come by very often, I decided it would be a nice change of pace to do it in full color.

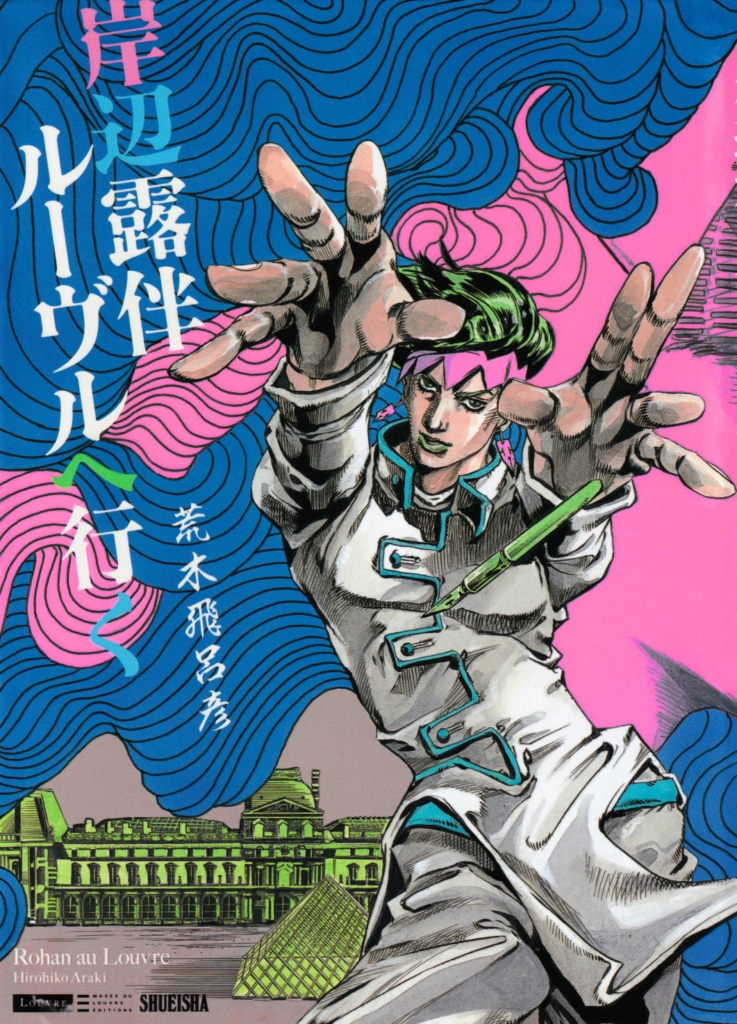

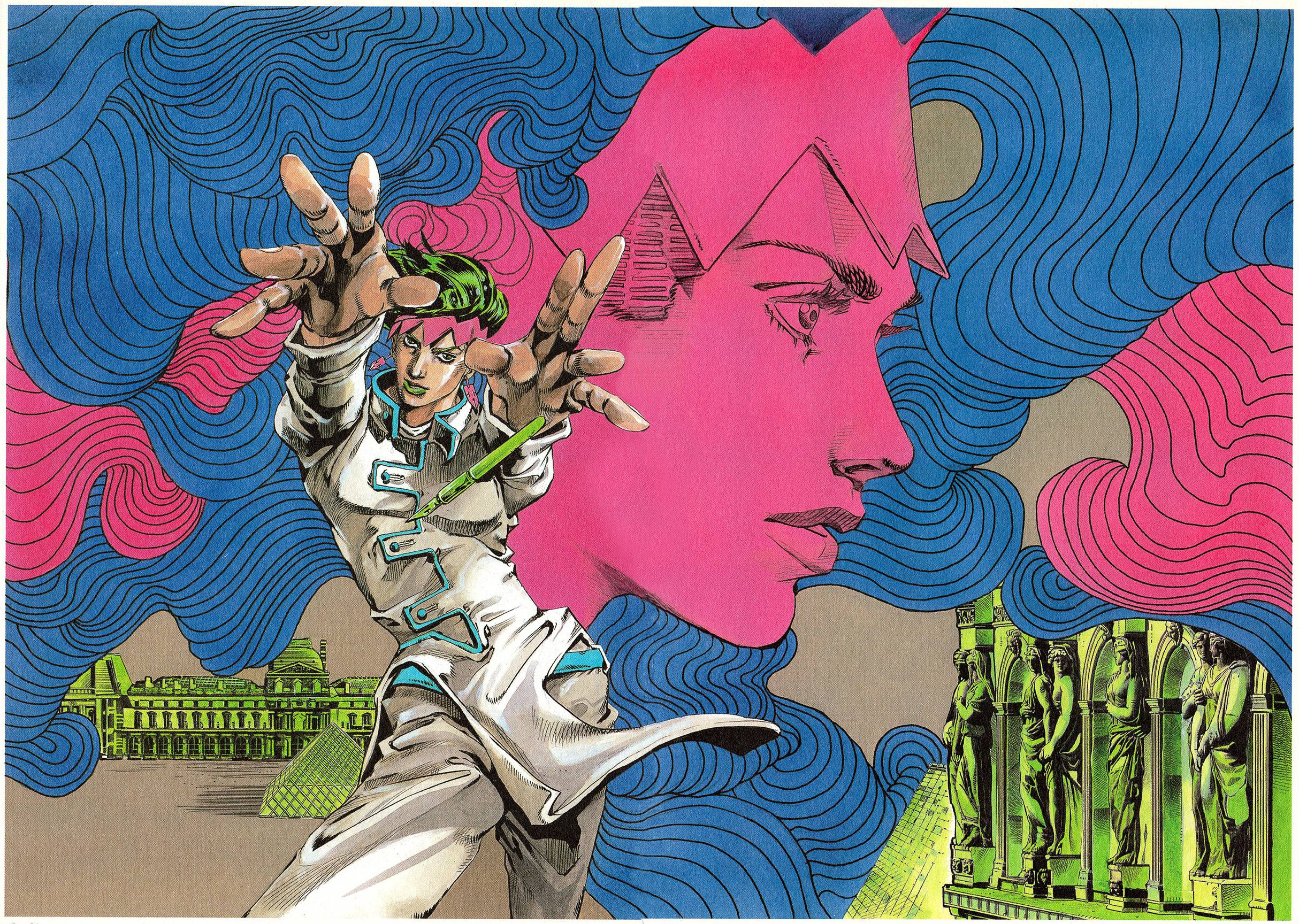

The illustration on the cover is very eye-catching, don’t you think?

Araki: The cover uses the three colors that symbolize France: white, red, and blue. Most old Japanese paintings feature a motif of clouds and waves, so I included a wavy pattern to give it a Japanese touch.

The colors in the story are a lot more subdued compared to the cover, aren’t they?

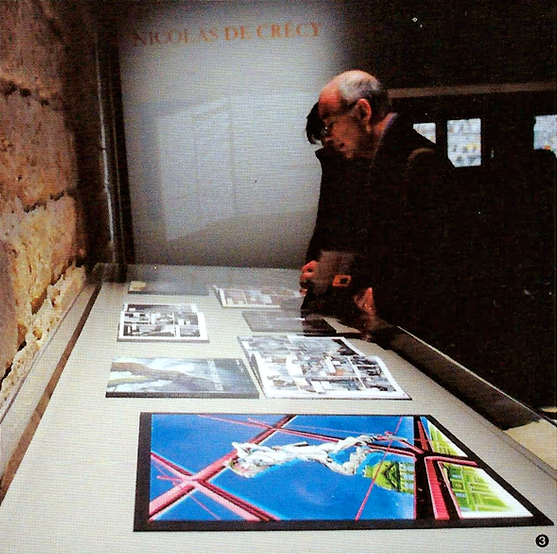

Araki: I figured that if I used my usual coloring method for the entire story, the readers would get tired of it, and that would be bad. So I decided to keep a balance that would encourage the readers to keep reading. I was given several French comic books to use as reference, such as works from Nicolas de Crécy, etc., which I studied to get a sense of drawing in full color.

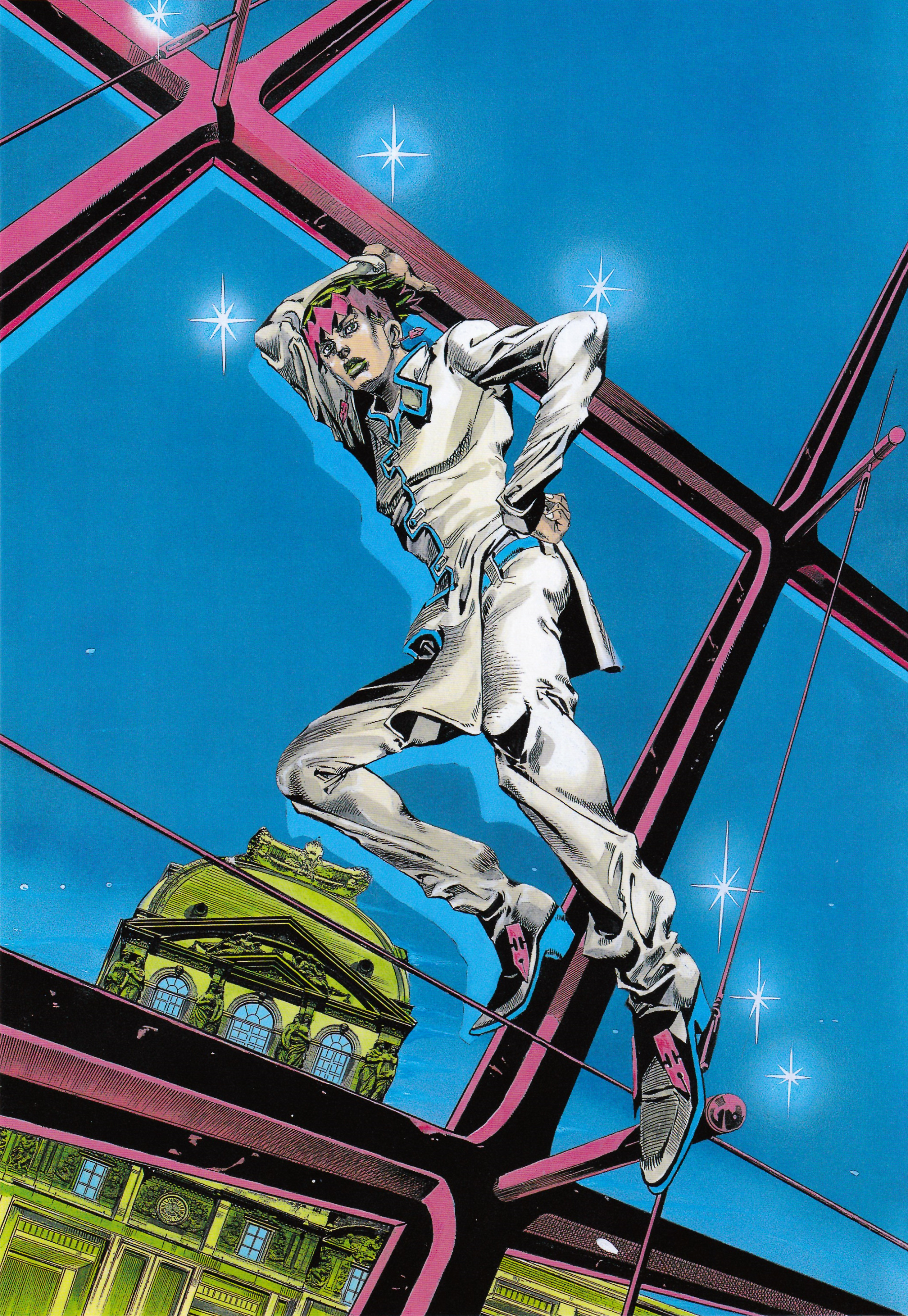

The story first takes place in Japan, then in the Louvre, and lastly underground.

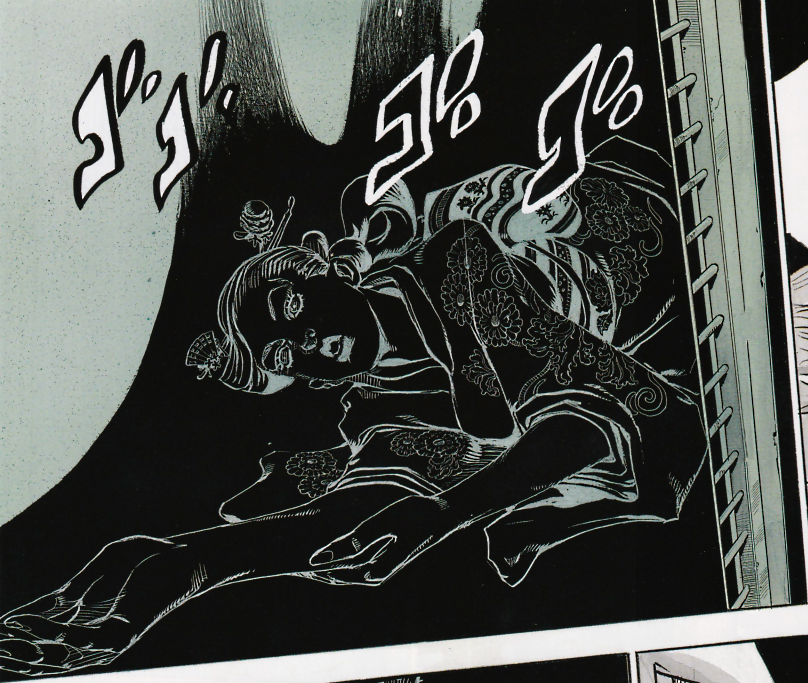

Araki: That’s right. The first part is the most Japanese as it takes place in Japan, and since it’s in the past, it has a sepia tone. I was conscious on what tones I should use for stuff like tatami mats. Once we arrive in Paris, it’s pink, and down in the underground, it’s blue. I did the first undercoat of paint the same for all parts of the story, and then later decided to split them into different colors.

In the book, we get to see many Japanese things, such as traditional Japanese houses and yukatas (summer kimonos).

Araki: I intentionally did this with French readers in mind. I don’t usually get to draw these types of things, so it was very refreshing and enjoyable.

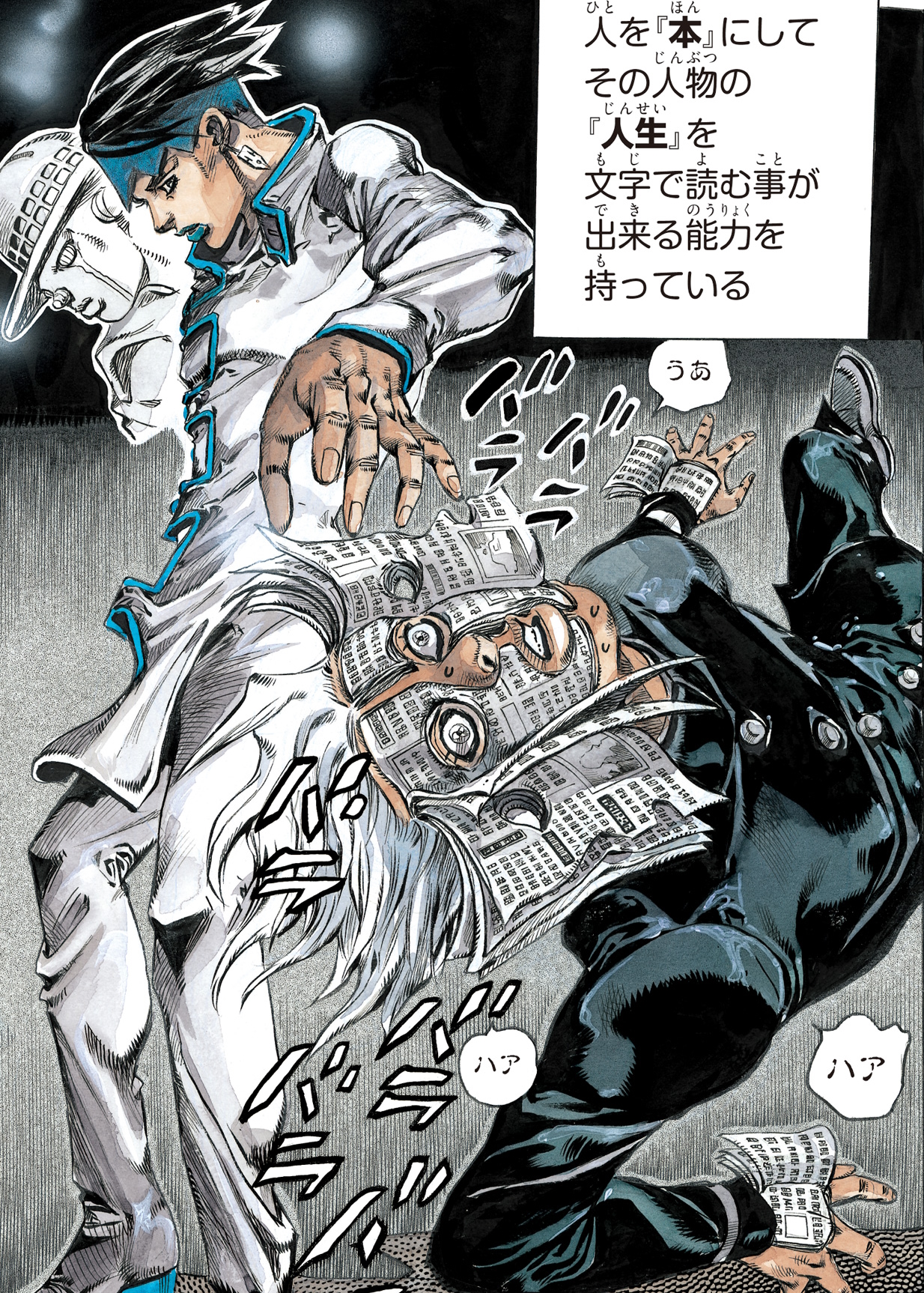

The main character is Rohan Kishibe, a manga artist from Part 4. Did you plan to have him as the protagonist from the start?

Araki: Well, they asked to create a new character, not one from JoJo. But I knew from the start that the story would be about a manga artist like Rohan going to the Louvre. So I thought, why not just use him? (laughs)

The combination of the Louvre and Rohan must’ve been a perfect match For Japanese readers.

Araki: Besides, had I created a new character from scratch, it would’ve taken a dozen pages to introduce them, and that would’ve made it a lot more difficult for readers to jump into the story. Also, if an author writes a character they’re familiar with, they can more easily present them to readers who have no idea who they are, like Rohan. I consulted this with the guys at the Louvre and managed to get them to approve it.

So you knew from the start what the plot was going to be?

Araki: Exactly. It was something along the lines of Rohan pursuing a mystery in the Louvre… But the Louvre is a fairly big place, so I had to narrow down the places I wanted to show. I thought it would be cool to feature a shady-looking underground area, and during his investigation, Rohan would have to go down into it from the upper floors.

At the time, I was curious where they kept all the paintings not on display. Those that were either not in perfect condition or were undergoing restoration not shown to the public. It made me wonder if something like the “black painting” in the story could be kept there.

The Rohan we see pursue the painting is a bit different from his eccentric self in Part 4. It was also interesting to see Rohan before his debut as a manga artist.

Araki: The Rohan I drew for the Louvre is a little different from the Rohan I drew for JoJo. However, there might’ve also been weird things this Rohan did that didn’t make it into the story. (laughs)

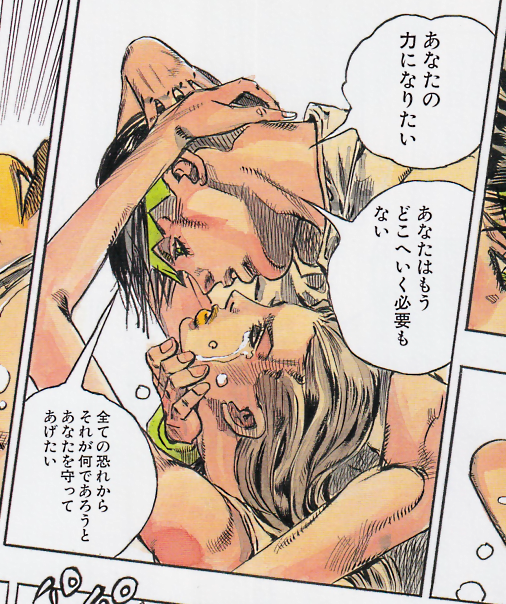

Rohan’s first love was never shown before, but we got to see her in the story.

Araki: I mostly associate French films with “erotic thrillers,” which feature some sort of secret love or affair. Something similar exists in Japan, although I wonder if it originated from France. Because of this, I put a bunch of old romance tropes throughout the story. (laughs)

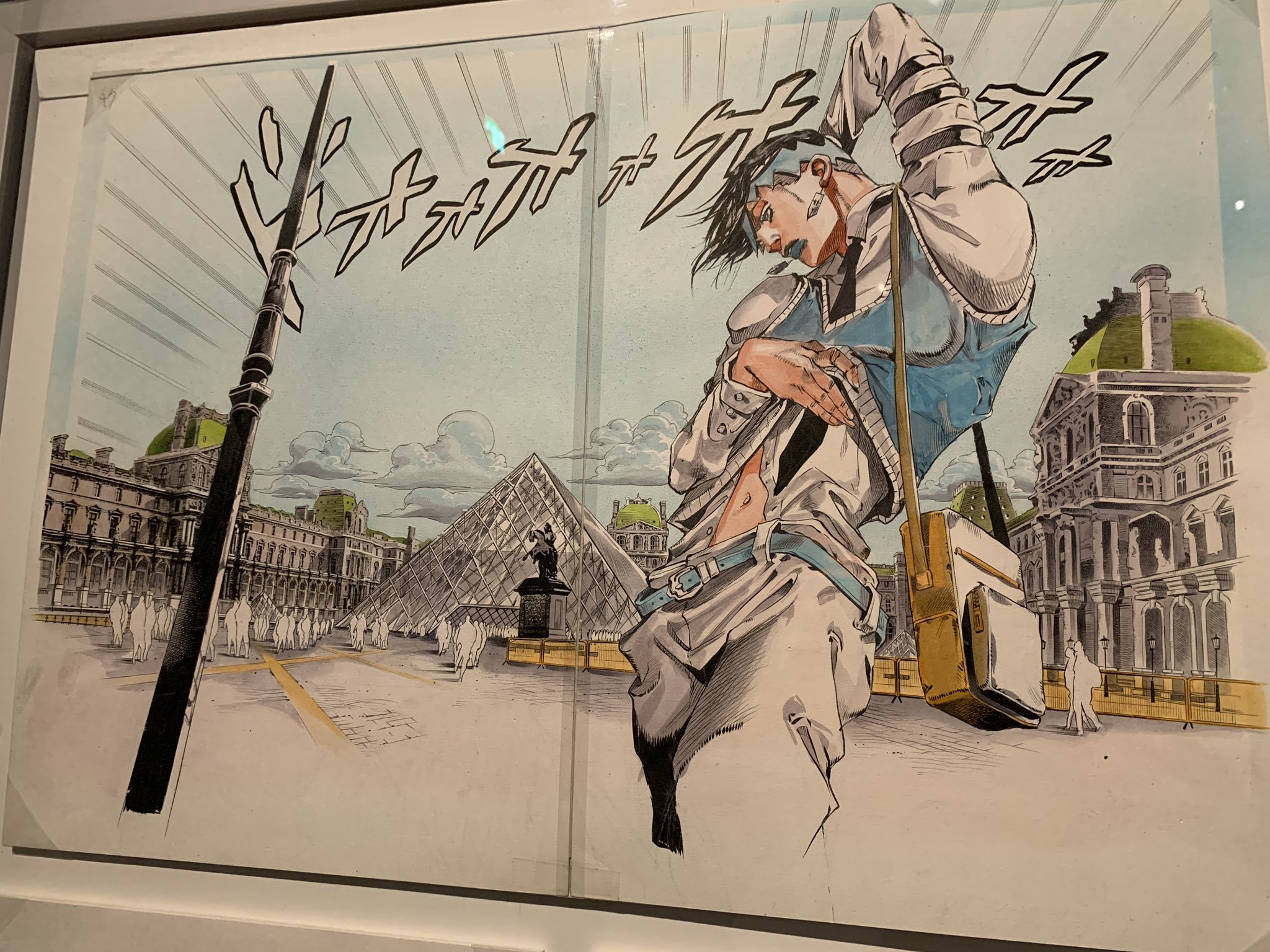

The story features a lot of poses, such as in the spread where Rohan arrives at the Louvre.

Araki: That pose was from Michelangelo’s “Dying Slave” sculpture. Since the book focuses on the Louvre, I tried paying homage to many of the works in its collection.

The scene where Rohan tries to read Nanase‘s memories was also inspired by Antonio Canova’s sculpture “Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss.” I added more references here and there, so I would be pleased if you tried looking for them all.

How did you feel exhibiting your works in front of French comics for the first time?

Araki: As one of the few Japanese artists presenting their works, I felt I had to give it a distinct and Japanese look. That’s why I came up with the idea of it taking place in Japan and then the Louvre, connecting the two.

What were some of the differences you found between French comics and manga?

Araki: The most obvious would be how the cover illustrations are presented. I was surprised when the Louvre asked me to draw mainly landscape artworks. When I looked at other works, I saw that they were mostly drawn wide with small characters, which is the exact opposite of the methodologies used in Japanese manga.

What do you think are some of the characteristics of French comics?

Araki: I think it’s the pursuit of drawing something in a way never done before. In the case of Japanese manga, the goal is to draw something that the readers will accept, but French comics ignore this and do the total opposite. It’s very liberating, and it forces you to go out and draw whatever way you want. That’s what differentiates it from Japanese manga.

Did your impression of the Louvre change after the exhibit?

Araki: Not at all. I’ll still keep wondering if there are hidden passages behind the walls, despite having been behind the scenes myself. After all, the Louvre is still the Louvre.

How do you feel about having your paintings exhibited in the Louvre?

Araki: I’m in awe. (laughs) The Louvre is a place that even Gauguin and Picasso couldn’t get into because it only exhibits pre-modern works. It’s truly an honor to have my art shown in the same place as the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo.

[Translated by Morgan (JoJo’s Bizarre Encyclopedia)](Photos taken by Didier Plowy & Scans provided by Fr0stiFusionZ)

Archival Footage

Full Transcript

Fabrice Douar: “Comics are not just a funny thing, they’re of all different kinds. There are humorous comics and they are perfect in their own genre, but there are also contemporaneous comics, which belong rather to creation, there are graphic novels, there are thrillers, there’s Manga, and here it’s not entertainment anymore, it’s about the exchange between an author and a reader like in any form of art, an exchange between a creation and its audience. So comics are not always just funny or entertaining, and the Louvre museum isn’t always dusty and boring.

What defines art? It’s funny because we’ve always wondered. When photography appeared, the question was : ‘is photography an art?’ Cinema took an incredible long time to establish itself as an art when today no one could question that. Comics are an art like other arts, it’s not the contemporary art, it is one of the contemporary arts. And what distinguishes comics from those others? Nothing much. There are only authors that use their hands for most of them since they draw, they use a pencil, colours, felt-tip pens, even watercolour, and with that they construct a story.”

Bernar Yslaire: “For anyone who does plastic arts and expose at the Louvre, it’s a consecration. And it’s the first time comics are presented at the Louvre so it’s even more prestigious to be one of the four who are supposed to represent comics here.”

About Rohan au Louvre

Before Ultra Jump published the manga on March 19, 2010, The Louvre Invites The Comics exhibit displayed Hirohiko Araki’s Rohan au Lovure at the Louvre Museum from January 22 to April 13, 2009.

The Louvre offered Araki to draw a manga to feature in their “bande dessinée” collection, making it the first manga published by Musée du Louvre Editions. Moreover, the manga is Araki’s first full-color work.

On January 4, 2023, a live-action film adaptation of Rohan au Louvre was announced. The film will premiere on May 26, 2023, and will star Issey Takahashi as Rohan Kishibe, as well as Marie Iitoyo as Kyoka Izumi.